Experience in LLM-assisted software development

December 2024

Just as electricity transformed almost everything 100 years ago, today I actually have a hard time thinking of an industry that I don’t think AI will transform in the next several years 1

In the last three months, I’ve put this claim to the 💪🏻 test. At least modestly so. Dusting off old personal projects and starting new ones, I decided to explore how LLM-powered tools could enhance software development. The result? A mix of powerful insights, frustrating hiccups, and plenty of learning opportunities. While the tools show incredible promise, they also highlight the challenges that come with relying on AI in development workflows.

For some context, I have been doing 🧑🏻💻 professional software development for about 15 years and stopped roughly a decade ago. I still write code as a hobby, it’s just too fun to drop completely. With all the rage about the new toys I decided to pick up a few opportunities to practice again and dive deeper. I had the following projects on the agenda:

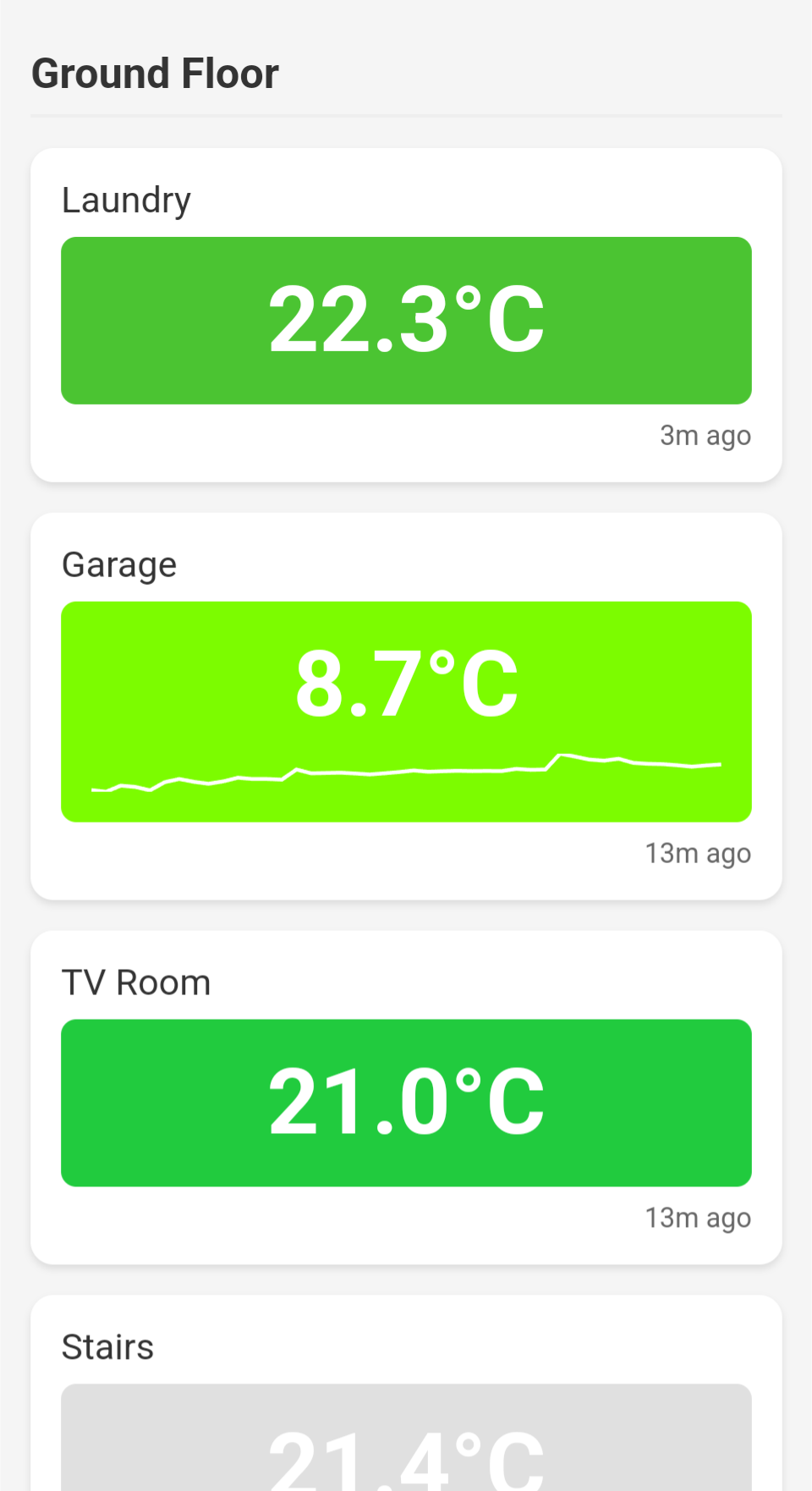

- Writing a very simple mobile-friendly web page displaying home temperatures

- Generating and charting stats for house energy prices over time

- Crafting and updating some CSS for my website

- Configuring server software on a few unix machines

- A file-renaming tool based on PDF content

There are many LLM tools out there, and surely more will surface, for now I tried the following:

I have decided not to venture into the territory of new languages or technologies I had no idea about. I stayed with

First, the good

Asking questions about the language-native ways of doing certain things in Python worked remarkably well. I could easily ask about list comprehensions, declaring lambdas, expressing conditions or using a more functional style. The answers were clear, helpful and got me unblocked quickly. I asked about what does “a feature I know from C# looks like in Python” or “How would you rewrite this JavaScript snipped in Python” and I always got an answer that worked. Gemini could do it, ChatGPT was very good and so was Claude, without a hiccup.

Using Python I relied on pandas2 and matplotlib3 for the data analysis and presentation. Finding out how to calculate or restructure something using DataFrames was faster than reading the documentation. Most of my charting needs were also met pretty well by the LLMs.

It was remarkably easy to understand what toolchains exist for Python these days - how to create virtual environments, how to declare and update dependencies or how to structure and package my code. It was much faster and more comprehensive than trying to google the right solutions or read-up on dozens of blog posts. LLMs also offered a high-level comparison between different options making it easy to choose between simple and more comprehensive solutions depending on a particular project’s needs.

With my PDF-renaming project I needed a way to parse the files. ChatGPT and Claude offered a solution that worked straight away. However, both offered them without any caveats around the suggested packages, we’ll come back to that later.

All tools did remarkably well when it came to tweaking or writing configuration for common linux server-side software such as apache or postfix. Suggestions around handling of virtual domains or hardening the security stance were in line with what I have already done in the past. There were no nasty surprises and no obvious blunders.

The web temperature display was a project that required some HTML frontend, styled with responsive CSS and complemented with client-side JavaScript to fetch the data. It also required very simple backend code to fetch the data from a couple of integrations. This was the biggest project and I started it out with Claude. Its integration of Markdown in the input field and presenting generated code in a side panel worked particularly well. It drafted and then tweaked both HTML and CSS for me quickly and easily rendering a prototype right in the UI. This allowed me to iterate quickly and add features smoothly. When I found a colour palette I wanted to use I could just drop an image of the colour-to-temperature scale and get all the colour codes and logic out with no sweat. That was probably the most impressive step. When the app grew a little larger and I told Claude I wanted there to be a more robust file structure it was time to move to Cursor. The desktop app is obviously the most complete and sophisticated tool of all I tried up-to-this point. Given that it’s based on VS Code I welcomed the familiar interface. The addition of LLM logic takes it up a notch in terms of usability. The auto-completions are really well designed and offer a significant improvement to the auto-complete experience of copilot I tried briefly before.

Overall, using the different LLMs felt like working with the help of a fairly knowledgeable partner available at a moment’s notice all at my fingertips. Better still, a group of partners I could call upon based on their area of speciality. Suddenly the barrier for “asking the annoying simple questions about something that feels fundamental” disappeared. Not a trace of guilt about bothering someone else without having RTFM before. Even if that guilt would have been completely misplaced.

Then, the not-yet-there

Despite all the great initial experiences I am not ready to give-up on working with other smart people, reading documentation or writing some of the code myself. Here are some practical snags I have come upon that made me grow a little bit of scepticism.

When it came to data insights work, more detailed questions about restyling graphs, applying different colours or layouts were more problematic. I would usually get an answer that worked but felt too clunky or sometimes one that didn’t quite work. In some cases the suggested snippet was enough to find the right place in matplotlib documentation to get the effect I wanted. In other cases I added another prompt or a follow-up on the offered code example. “This works, but use subplots() to create the figure”, or “Surely, there is a better way to define colors here”. These are literal prompts I used and they were helpful. Mind you, I have seen and written enough of these bits of code to have a feel for what looks good and notice when something is too complex or not quite right.

I alluded to a concern about package selection earlier. It’s time to elaborate on the topic. For the PDF parsing both Claude and ChatGPT offered functional solutions but made no remarks on the specific libraries suggested or existence of alternatives. I had to prompt it explicitly to ask about the security stance, maintenance or support that suggested packages provided. Only then LLMs complimented me on my diligence and offered a more balanced view of alternatives. This kind of thinking comes with years of experience and has clearly not yet been “encoded” into the models. For hobby projects it’s just mildly annoying when the selected library stops working with a new version of the language. For anything commercial, including packages that pose a potential security threat is much more of a problem.

I was always very rigorous with writing automated tests as a professional developer. After I learnt and practiced TDD sufficiently it has become my favourite and most productive workflow. For very small prototypes, the kind of work I do now, I admit to sometimes skipping on tests. Having LLMs at my side promised an opportunity to rectify that. Indeed getting the test setup in place and integrating build tooling was very fast. The actual test code suggested by LLMs is a whole other story. It felt overly complex, unreadable and most importantly brittle. It wasn’t expressed in the language of the domain. On the other hand, with enough follow-up prompting I did manage to get to a decent state with a couple of tests. With more practice I’m confident I would write better tests much more quickly by hand.

There is one more problematic pattern I have spotted with all three LLMs. Every now and then I would bump into some deprecated API that the original generated code included. I would write a prompt to fix it, something like “This code snippet you just shared includes use of a deprecated method X”. Most notoriously with date & time operations in Python. At other times it would generate code that just didn’t work, or didn’t work as expected. Somehow that surfaced most with node.js APIs around processing streams. No amount of nudging would get to the right answer. Rather, the LLM would apologise for the mistake and offer an alternative that also didn’t work. When I tried correcting that again, it would go back to the first wrong answer effectively stuck in a loop of wrong answers.

CSS proved to be one of the more frustrating aspects of my experiments. While the LLMs could handle simple, common patterns with ease, they often fell short when I needed something more nuanced or semantic. Writing a clean, well-structured stylesheet seemed almost impossible with their help. Instead, I’d get solutions that were functional but far from optimal.

This highlights a broader limitation: LLMs excel at solving well-defined problems with clear patterns but struggle with tasks requiring subjective judgment or creative problem-solving. CSS, often an art as much as a science, exposes these shortcomings more than many other areas of development.

Why is it so?

These new large language models are trained on huge amounts of data, including loads of open-source code. Open source has been a massive force for innovation. But it’s not all perfect. A lot of open-source projects are built with limited resources and people’s casual contributions, so you’ll often find code that’s inconsistent, poorly documented, or missing robust automated tests.

This creates a feedback loop for LLM-generated code. When models are trained on a mix of well-crafted and hastily written code, their outputs naturally reflect that mix. For example, Python’s deprecated datetime.utcnow() appears in hundreds of thousands of GitHub files, while the recommended datetime.now(tz=datetime.UTC) is far less prevalent. These patterns shape what LLMs see as “normal,” resulting in recommendations that often prioritise familiarity over good practices.

It’s not a dig at the open-source community, which thrives on passion and voluntary contributions. The problem is more about how this data is used to train the models. Until we figure out ways to feed these models better-quality examples or teach them to spot “what good looks like,” LLMs are best used as a boost for developers who already know their way around. If you’re not careful, though, you might end up relying on advice that could cause bigger issues down the line.

What next?

It’s amazing to see this technology evolve. With new versions of the models released regularly I’m already seeing some of the experiences I describe so far to be shifting in a positive direction. Which is why I will continue trying these tools out to experience how they change and evolve. I also want to understand how engineers can most effectively and productively incorporate them into their workflows. As a popular adage has it - we should not be worried of AI taking over the jobs, but of the people using AI.

If, like me, you are a 🧑🏻💼 leader in an engineering organisation today - well, thank you for making it thus far. I hope you are encouraging and enabling your teams to practice with these new tools. Support them in capturing the experience, sharing it broadly and in creating a space for discussions and learning.

And on point, this post is published right as GitHub has announced the availability of GitHub Copilot in Visual Studio code for 💸 free.

✨ Now is the perfect time to give it a try. ✨